Are you one pancake shy of a full stack? If your web-based internal tools have a distinctly by-engineers-for-engineers aesthetic, and you want to rapidly create more-attractive and intuitive apps, it’s well worth your time to learn ReactJS. That’s what I did while creating a dashboard for viewing current, upcoming and previous releases for the mobile platforms.

I work in the Developer Efficiency group at Credit Karma. Our mission is to reduce friction for developers to get their work deployed to production in a quality manner. A great way to build quality into the product is to make it painless for everyone (Design, Development, Product Management, Quality Engineering) to try out features in an environment that is as similar to production as possible.

With a member base of more than 85M, many of which use Credit Karma on their mobile device, it’s also important to know which new features have been released, and when. We have a rapid-release cadence for mobile app updates — it’s critical to know which features are coming online at what rate so that they, and the services upon which they rely, can be monitored.

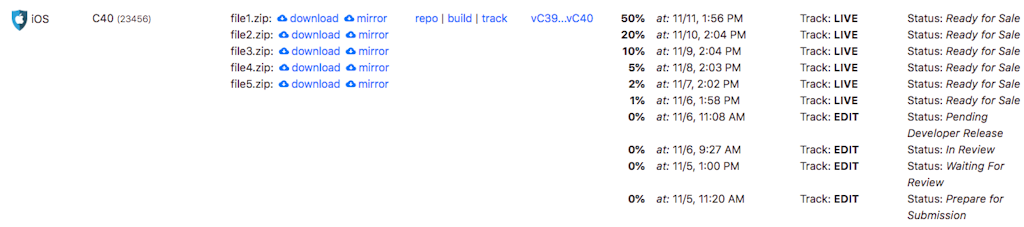

When a new update is released to production, it isn’t downloaded to all users simultaneously; it’s made available gradually to those users who choose to update. Last year, Apple made it possible to do phased releases directly from the App Store, starting with a 1% ramp and increasing up to 100% over seven days. Google’s Play Store has a similar capability called staged rollouts, which can be modified and monitored using the extensive Google Play Developer API.

We found that our teams frequently needed to know what ramp percentage (which phase of the release) a given update was at, and when those ramp levels changed. Conversations in the native team Slack channel suggested that people would benefit from an automated way to update the status of production rollouts of iOS apps. In talking to the team, we learned that PMs logged in to App Connect, located the ramp percentage, informed the team and other interested parties via Slack, and manually updated a wiki page. This might take place several minutes or sometimes hours after the fact. We wanted to provide visibility into that information, to all interested parties, in real time.

Further, people looked in different places to get the info they needed about where to download builds, and which features were included in a given version. We felt we could provide all of this information in a single place in a compact format, without the need for any manual updating.

This was my first ReactJS project, and serves as a front-end to a database and API we built to collect and make available data about our CI/CD pipeline. I am more comfortable with back-end technologies, and while I’ve created satisfactory web-based UIs that served their intended purposes, I wanted this dashboard to have a wider reach with a truly discoverable UI. I never expected to be extolling the virtues of JavaScript, having been patiently awaiting its demise for (consults wrist) about two decades … yet here we are!

I learn best by reading docs and doing tutorials. To improve my JS skills, I dug in to the vast JavaScript resources on MDN Web Docs. As luck would have it, around that time Credit Karma University offered an internally conducted course on JavaScript conducted by one of our staff SWEs. Once I’d done some remedial JS, I was ready for the ReactJS tutorial. With a ton of in-house FE and ReactJS expertise, I sought input frequently and enjoyed some paired programming sessions with my teammates.

During the project, I heard from a coworker about a day-long workshop, Building Data Visualizations with React + D3. The culture of learning at Credit Karma is no joke. We get money to spend every year on professional development activities and materials, so a quick manager acknowledgement was all I needed to make it happen. The focus was on building time-series visualizations, which I will be doing in a future iteration of the dashboard. It was great timing for me to be able to walk through an expert’s ReactJS code.

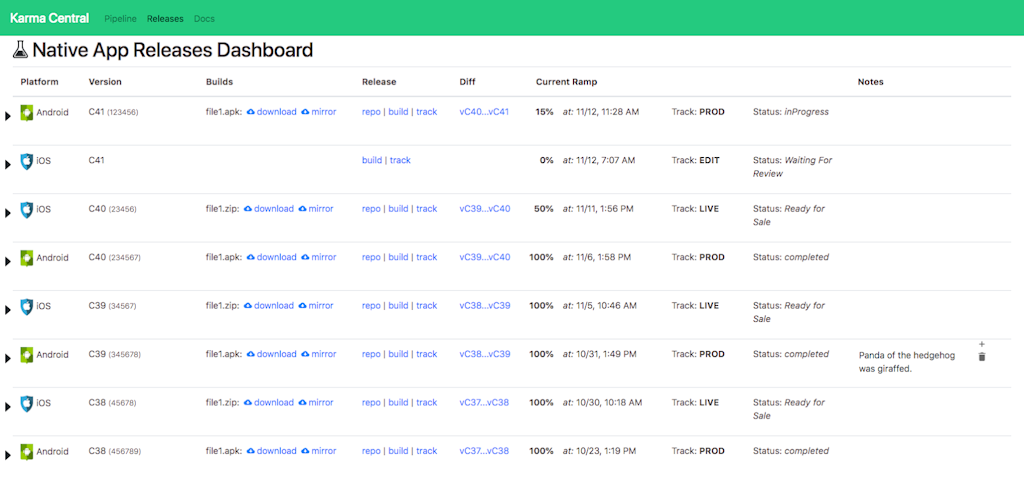

Meanwhile, I looked at the information people had recorded on the wiki page and in the Slack channel and laid it out in a table that contained, at minimum, the same information that was on the wiki.

Each row is a version for a platform. For example, see version C40 for iOS in figure 1. The row summarizes the current status of that platform/version, and can be expanded to show the ramp history and other detail, shown in figure 2. A Bootstrap collapse component handles the work of showing/hiding the detail.

We were already storing information from continuous integration runs, as well as release information from repository webhooks. This was our opportunity to flesh out the data with more information from the pipeline stages, and also to collect the ramp details from the mobile stores. For the Android apps, we periodically poll for the latest ramp levels using the Google API Client Library for Python. To do the same for iOS apps, we wrapped in Python this Ruby script that gathers the info from App Store Connect using Fastlane’s Spaceship.

The data is stored in PostgreSQL and an API written in Python accesses it through SQLAlchemy ORMs. The API and dashboard endpoints are served with Flask, and the front-end components are in ReactJS and Bootstrap. If you’re interested in serving a ReactJS front end with Flask, here’s an easy starter project.

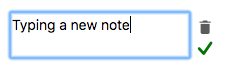

While we now had an app that collected and displayed information automatically, we also needed to provide a way for people to annotate a release in the event that it was paused, or if the team needed to record other special information about it. This notes field was the part that took the longest to get right. It needed to feel natural to add/edit/delete notes while being hard to accidentally wipe out information. This went through a few iterations and lots of internal testing. To keep the UI in sync with the database, the Note component employs the componentDidUpdate() lifecycle event, and its container component refetches via axios after any user update. Elsewhere, the dashboard manages state as little as possible.

Because adding a note to an update row is a relatively infrequent event, we opted to keep it simple and not support concurrent note edits for this release. Support for that in the future will employ socket.io, which will allow us to impose database transactions from the server, and also provide feedback to any viewers of the page whenever another user is editing, similar to a chat application.

The app is in use by the native team, and we’re taking the deprecation of their old wiki page as a vote of confidence. The team gave us great feedback, which we’ll roll into future versions of the tool. Other improvements will include taking advantage of a library of ReactJS components developed in-house, adding timeline visualizations, and reusing the components for other applications of the back-end dataset and API.

Some key takeaways from building this dashboard:

- The power of ReactJS is worth pushing through its learning curve.

- As with any project, keep in touch with your user base and be prepared to act on feedback.